The first two acts of 2001: A Space Odyssey which we have been covering on recent Saturdays, function more as preludes. Act 3 is really where the story begins.

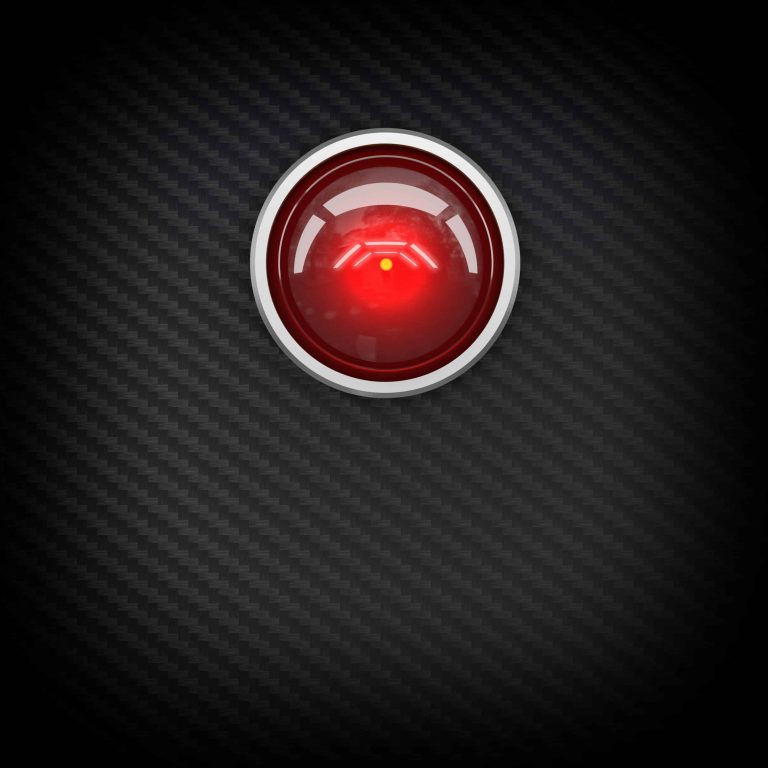

In the opening, Dr. David Bowman and his partner, Dr. Frank Poole are flying to Jupiter on their ship, Discovery One. It is piloted by humanity’s newest AI, the HAL 9000. There are also three other scientists on the ship — in hibernation. The plan is to wake them up once the crew reaches Jupiter. So far, things seem to be going well, although HAL immediately comes off as arrogant, declaring itself free from error multiple times as the story progresses.

Soon, HAL reports that a part of their satellite is about to malfunction. So Bowman and Poole go and replace the supposedly broken part. However, when they inspect the AE-35 unit, Bowman can’t find anything wrong with the device. Mission Control also confirms that the part does not appear to be broken. It looks like HAL made a mistake.

HAL cannot make errors

Of course, HAL is unwilling to admit such a thing, insisting the fault is a human error. This worries Bowman and Poole. Because HAL can hear everything aboard the Discovery, the two hide in one of the shuttles and turn off the communications. Inside the shuttle, they discuss what they’re going to do, and it doesn’t take them long to conclude that it would be best to shut HAL off.

Unfortunately for the two scientists, HAL can read lips.

HAL then tell them that there is another problem outside the Discovery. When Poole goes outside to fix the issue, HAL somehow ejects him from his shuttle, and he goes flying off into space. The tube supplying air to his space suit is also disconnected, but the audience is never told why. Bowman takes another shuttle to retrieve Poole, but it’s obvious that his friend is dead.

The famous scene at the door

After retrieving Poole’s body, Bowman returns to the ship. But when he asks HAL to let him back inside, HAL refuses.

Now, before moving on. I should discuss the subject of AI. Both Clarke and Kubrick treat AI as a potential threat to humanity, but for different reasons. Kubrick treats HAL as a very cold device that is basically protecting a set of secretive orders. He kills the hibernating scientists and Poole because — since he knows the true nature of the mission — shutting him off would risk the mission’s failure. Clarke has a different take. In the novel, he states that HAL’s secret orders were inconsistent with the AI’s prior programming, and the two opposing directives created a conflict inside the robot, something similar to a conscience. Because the machine is feeling something akin to guilt, he murders Poole in an attempt to cover up his lie about the broken AE-35 unit.

Both interpretations serve the narrative, the idea being that mankind’s greatest opponent is going to be the technology he created. Personally, I find Kubrick’s interpretation more persuasive. I don’t see a toaster forming a conscience, but I can see a robot choosing to prioritize conflicting orders. Mission Control’s directives would most likely override whatever prior programming he’d received.

Bowman must now enter the ship on his own, which he does with relative ease. Thankfully, Kubrick didn’t write his scientists as complete idiots. They weren’t stupid enough to give HAL full control of the ship. Bowman is able to reenter the ship through an emergency hatch and he immediately goes to the room where HAL’s hardware is located.

HAL slowly unwinding

He begins to turn HAL off, one floppy disk at a time, and here is probably the best scene in the movie. It’s certainly one of the most iconic, and for good reason. As Bowman deactivates HAL, the robot begins pleading with him, telling Dave that he is afraid. This is where Kubrick’s brilliance really shines. Is HAL really sentient, or does the robot think Bowman will be won over by sympathy? The audience doesn’t know. The movie never tells the audience what to think. If only more films were so clever.

The Monolith returns to center stage

Once HAL is turned off, a message from Heywood appears. Heywood explains the situation with the Monolith. The movie fades the scene before Heywood can give Bowman the full message, but the audience knows enough. Bowman needs to find whatever the Monolith on the moon was signaling to. It could be another Monolith. It could be something else. But either way, Bowman must uncover the truth.

The main complaint I have with this portion of the film is, as I mentioned last Saturday, is that the film could’ve benefited from showing HAL in a more positive light at the beginning. But the second act with Heywood had already established the positive aspects of technology so there was nothing to do but present HAL as an ominous threat. Right out of the gate, the robot puts off unsettling vibes, which works great with the atmosphere of the film. The viewer is constantly expecting something to go wrong. This is good. HAL’s voice and creepy demeanor serve the story well.

Again, I just feel the story would’ve been better if the positive and negative aspects of technology were both demonstrated through HAL directly. But, provided the viewer isn’t thrown off by the second act, the dichotomy is established well enough that HAL, as an ominous presence, still serves his intended purpose. This portion of the film is the most famous for good reason. It accomplishes what it’s intending to do.

But could AI really rival humanity?

Could the nightmare scenario represented by HAL actually happen? I believe that it all depends on how humanity treats AI. The film itself actually serves as a good example of what I mean. As long as mankind remembers that AI is a machine and things can go wrong, I don’t foresee any problems. As long as the scientists don’t give the robots full control of the ship, any issues that arise can be solved. But if mankind starts taking Clarke’s approach, I can see any number of terrible futures. The issue isn’t how advanced AI becomes; the issue is whether or not mankind will be foolish enough to try and build its own god, one made of hooks and wire, rather than wood and gold. When Bowman reaches Jupiter, he sees the Monolith floating in space. We will look at what happens then next Saturday.

Here’s the first part of my review: 2001: A Space Odyssey was a new type of science fiction, The film is perhaps best understood as three completely different stories whose only connection is the monolith. The greatest measure of a film’s success is the test of time. Something about this film works even though it breaks conventions.

Here’s the second: Space Odyssey 2001: Decisions to make about that Monolith. In Part 2 of my series on the sci-fi great, I want to consider where the Monolith fits in the hard vs. soft magic systems that make for sci-fi stories. Letting the question of who sent the monolith remain a mystery was probably a wise dramatic choice on the part of the writers.

The third: Space Odyssey 2001: Were Clarke and Kubrick at odds? Part 3: The ambiguity in 2001 is not the result of artistic muddiness but the middle ground for an unspoken conflict between the two writers. One thing is for certain. In the iconic Dawn of Man sequence, the Monolith is conveying information. The question is how.

And the fourth:

2001: A Space Odyssey: The Brief Story of Heywood Floyd. In Part 4, we look at what the middle story — meeting the Monolith on the moon — is doing. We don’t really get to see enough of HAL 9000 when he is actually a help to the space travelers, which reduces the impact of his turn.